読んだ本

Concurrency in Go

Tools and Techniques for Developers

http://shop.oreilly.com/product/0636920046189.do のkindle版

sample codeはこちらで公開されています

https://github.com/kat-co/concurrency-in-go-src

自分の英語とgoの理解度で、わかる範囲のメモです。

Difference Between Concurrency and Parallelism

Concurrency is a property of the code; parallelism is a property of the running program.

[Cox-Buday, Katherine. Concurrency in Go: Tools and Techniques for Developers (p. 23). O'Reilly Media. Kindle Edition. ]

we do not write parallel code, only concurrent code that we hope will be run in parallel. Once again, parallelism is a property of the runtime of our program, not the code.

[Cox-Buday, Katherine. Concurrency in Go: Tools and Techniques for Developers (p. 24). O'Reilly Media. Kindle Edition. ]

Concurrencyとparallelismの違い(並列実行と並行実行の違い)について、よく理解できていませんでしたが、この説明がいまのところ一番しっくりきています。参照透過性やクロージャーでもそうでしたが、なにか学術的な概念が背後にある用語はみなさんの説明がいろいろばらばらなことが多く、並列と並行もその類のものでしたが、ひとまずはこの理解でこの用語を理解しておくことにしようと思っています。

What is CSP

Communicating Sequential Processesの略ということだけしかわかりませんでした。

わかりやすい説明をご存知の方がおられましたら、教えてください。

paper

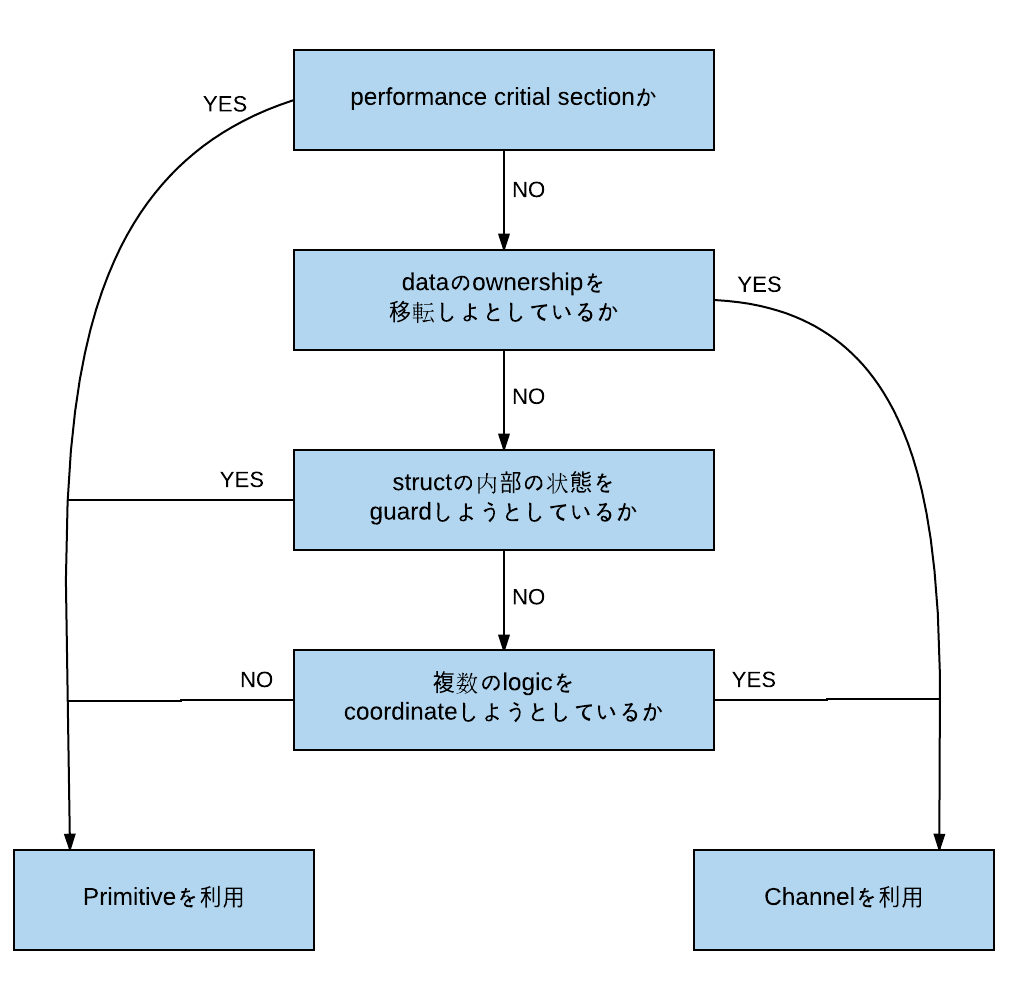

channelとsync.Mutex どっちを使えばいいのか

concurrentなcodeをかく場合にchannelを利用するかsync.Mutexを利用するかの判断基準の一例

Go's philosophy on concureency

Go's philosophy on concurrency can be summed up like this: aim for

simplicity, use channels when possible, and treat goroutines like a free

resource.

[Cox-Buday, Katherine. Concurrency in Go: Tools and Techniques for

Developers (p. 36). O'Reilly Media. Kindle Edition.]

Gorutines

They're not OS threads, and they're not exactly green threads ---

threads that are managed by a language's runtime --- they're a higher

level of abstraction known as coroutines. Coroutines are simply

concurrent subroutines (functions, closures, or methods in Go) that are

nonpreemptive --- that is, they cannot be interrupted. Instead,

coroutines have multiple points throughout which allow for suspension or

reentry.

What makes goroutines unique to Go are their deep integration with Go's

runtime. Goroutines don't define their own suspension or reentry points;

Go's runtime observes the runtime behavior of goroutines and

automatically suspends them when they block and then resumes them when

they become unblocked. In a way this makes them preemptable, but only at

points where the goroutine has become blocked. It is an elegant

partnership between the runtime and a goroutine's logic. Thus,

goroutines can be considered a special class of coroutine.

[Cox-Buday, Katherine. Concurrency in Go: Tools and Techniques for

Developers (p. 38). O'Reilly Media. Kindle Edition. Cox-Buday,

Katherine. Concurrency in Go: Tools and Techniques for Developers (p.

38). O'Reilly Media. Kindle Edition.]

coroutine(pythonで聞いたことあるあれか)というものの、特殊なものがgoroutineということらしい。

goroutineの特徴として

- a few kilobytes per goroutine

- the garbage collector does nothing to collect goroutines that have

been abandoned

ということで、goroutineは気軽に作成してもいいが、gcの対象にならないからgoroutine leakに注意しようということ。なので、done channel(ひいてはcontext)を渡そうという話しにつながる。

sync package

Cond

func main() {

button := Button{Clicked: sync.NewCond(&sync.Mutex{})}

subscribe := func(c *sync.Cond, fn func()) {

var goroutineRunning sync.WaitGroup

goroutineRunning.Add(1)

go func() {

goroutineRunning.Done()

c.L.Lock()

defer c.L.Unlock()

c.Wait()

fn()

}()

goroutineRunning.Wait()

}

var clickedRegistered sync.WaitGroup

clickedRegistered.Add(3)

subscribe(button.Clicked, func() {

fmt.Println("Maximizing window.")

clickedRegistered.Done()

})

subscribe(button.Clicked, func() {

fmt.Println("Displaing annoying dialog box!")

clickedRegistered.Done()

})

subscribe(button.Clicked, func() {

fmt.Println("Mouse clickded.")

clickedRegistered.Done()

})

button.Clicked.Broadcast()

clickedRegistered.Wait()

}

Wait() の中で、blockする前にUnlock()を呼んで、blockが終わりWait() から抜けるときにLock() を呼んでいる。どういうところで利用されているのか知りたいので,standard packageやthird packageで利用されている例をご存知の方がおられましたら教えてください。

Once

本書の内容から逸れてしまいますがGoでsingleton patternをやろうとする際に

var conn *SomeConn

func GetConn() (*SomeConn, error) {

var err error

if conn == nil {

conn, err = NewSomeConn()

}

return conn, err

}

のようにやっていたのですが、これだとgoroutine

safeでないので、Onceを利用して以下のようにやるようにしています。

var (

conn *SomeConn

once sync.Once

)

func GetConn() *SomeConn {

var err error

once.Do(func() {

conn, err = NewSomeConn()

})

return conn, err

}

Pool

func connectToService() interface{}

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

return struct{}{}

}

func warmServiceConnCache() *sync.Pool {

p := &sync.Pool{

New: connectToService,

}

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

p.Put(p.New())

}

return p

}

func startNetworkDaemon() *sync.WaitGroup {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

connPool := warmServiceConnCache()

server, err := net.Listen("tcp", "localhost:8080")

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("cannot listen: %v", err)

}

defer server.Close()

wg.Done()

for {

conn, err := server.Accept()

if err != nil {

log.Printf("cannot accept connection: %v", err)

continue

}

svcConn := connPool.Get()

fmt.Fprintln(conn, "")

connPool.Put(svcConn)

conn.Close()

}

}()

return &wg

}

func init() {

daemonStarted := startNetworkDaemon()

daemonStarted.Wait()

}

func BenchmarkNetworkRequest(b *testing.B) {

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

conn, err := net.Dial("tcp", "localhost:8080")

if err != nil {

b.Fatalf("cannot dial host: %v", err)

}

if _, err := ioutil.ReadAll(conn); err != nil {

b.Fatalf("cannot read: %v", err)

}

conn.Close()

}

}

生成にcost(memoryや時間)がかかり、使いまわせるならstructなら汎用的に使えそうなので、是非利用してみたいです。bytes.Bufferを Reset と併せて、利用されているsampleもみたことがあります。

Channel

Channel Operation

| Operation | Channel state | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Read | nil | Block |

| Open and Not Empty | value | |

| Open and Empty | Block | |

| Closed |

<default value>, false |

|

| Write Only | Compilation Error | |

| Write | nil | Block |

| Open and Full | Block | |

| Open and Not Full | Write Value | |

| Closed | panic | |

| Receive Only | Compilation Error | |

| close | nil | panic |

| Open and Not Empty | Close Channel; read succeed until channel is drained, then reads produces default value | |

| Open and Empty | Close Channel; reads produces default value | |

| Closed | panic | |

| Receive Only | Compiration Error |

- closeされたchanにwrite

- nil chanをclose

- closeされたchanをclose

がpanicになるので注意が必要

select statement

- 複数のchannelから値がreadできる状態の場合

func main() {

c1 := make(chan interface{})

close(c1)

c2 := make(chan interface{})

close(c2)

var c1Count, c2Count int

for i := 1000; i > 0; i-- {

select {

case <-c1:

c1Count++

case <-c2:

c2Count++

}

}

fmt.Printf("c1Count: %d\nc2Count: %d\n", c1Count, c2Count)

}

実行結果:

c1Count: 515

c2Count: 485

randomに実行されるcaseが選択される

- どのchannelもreadyにならない場合

blockし続ける. defaultがあればdefaltが実行される.

Preventing Gorutine Leaks

goroutineのtermination path

- When it has completed its work

- When it cannot continue its work due to an unrecoverable error

- When it's told to stop working

func main() {

newRandStream := func(done <-chan interface{}) <-chan int {

randStream := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer fmt.Println("newRandStream closure exited.")

defer close(randStream)

for {

select {

case randStream <- rand.Int():

case <-done:

return

}

}

}()

return randStream

}

done := make(chan interface{})

randStream := newRandStream(done)

fmt.Println("3 random ints:")

for i := 1; i <= 3; i++ {

fmt.Printf("%d: %d\n", i, <-randStream)

}

close(done)

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

}

実行結果:

3 random ints:

1: 5577006791947779410

2: 8674665223082153551

3: 6129484611666145821

newRandStream closure exited.

If a goroutine is responsible for creating a goroutine, it is also

responsible for ensuring it can stop the goroutine.

[Cox-Buday, Katherine. Concurrency in Go: Tools and Techniques for

Developers (p. 94). O'Reilly Media. Kindle Edition.]

goroutineを作成する側がそのgoroutineを適切に終了させる責任を負うとすれば、goroutine leakは防げるので、done(context)を渡すのが基本になる。

The or-channel

func main() {

var or func(channels ...<-chan interface{}) <-chan interface{}

or = func(channels ...<-chan interface{}) <-chan interface{} {

switch len(channels) {

case 0:

return nil

case 1:

return channels[0]

}

orDone := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

defer close(orDone)

switch len(channels) {

case 2:

select {

case <-channels[0]:

case <-channels[1]:

}

default:

select {

case <-channels[0]:

case <-channels[1]:

case <-channels[2]:

case <-or(append(channels[3:], orDone)...):

}

}

}()

return orDone

}

sig := func(after time.Duration) <-chan interface{} {

c := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

defer close(c)

time.Sleep(after)

}()

return c

}

start := time.Now()

<-or(

sig(2*time.Hour),

sig(5*time.Minute),

sig(1*time.Second),

sig(1*time.Hour),

sig(1*time.Minute),

)

fmt.Printf("done after %v", time.Since(start))

}

実行結果:

done after 1.000755189s

複数のdone channelを監視したいときのpattern.

Error Handling

I suggest you separate your concerns: in general, your

concurrent processes should send their errors to another part of your

program that has complete information about the state of your program,

and can make a more informed decision about what to do.

[Cox-Buday, Katherine. Concurrency in Go: Tools and Techniques for

Developers (p. 98). O'Reilly Media. Kindle Edition.]

type Result struct {

Error error

Response *http.Response

}

func main() {

checkStatus := func(done <-chan interface{}, urls ...string) <-chan Result {

results := make(chan Result)

go func() {

defer close(results)

for _, url := range urls {

var result Result

resp, err := http.Get(url)

result = Result{Error: err, Response: resp}

select {

case <-done:

return

case results <- result:

}

}

}()

return results

}

done := make(chan interface{})

defer close(done)

urls := []string{"https://qiita.com/", "https://badhost"}

for result := range checkStatus(done, urls...) {

if result.Error != nil {

fmt.Printf("error: %v", result.Error)

continue

}

fmt.Printf("Response: %v\n", result.Response.Status)

}

}

実行結果:

Response: 200 OK

error: Get https://badhost: dial tcp: lookup badhost: no such host%

Again, the main takeaway here is that errors should be considered

first-class citizens when constructing values to return from goroutines.

If your goroutine can produce errors, those errors should be tightly

coupled with your result type, and passed along through the same lines

of communication --- just like regular synchronous functions.

[Cox-Buday, Katherine. Concurrency in Go: Tools and Techniques for

Developers (p. 100). O'Reilly Media. Kindle Edition.]

起きうる結果を表現できるstructを用意して、producerのgoroutineから

concerns of error handlingを分離する.

どこでerror handlingするかいつも迷ってしまうので、この考え方は非常に参考になりました。

Pipelines

By using a pipeline, you separate the concerns of each stage, which

provides numerous benefits. You can modify stages independent of one

another, you can mix and match how stages are combined independent of

modifying the stages, you can process each stage concurrent to upstream

or downstream stages, and you can fan-out, or rate-limit portions of

your pipeline.

[Cox-Buday, Katherine. Concurrency in Go: Tools and Techniques for

Developers (p. 101). O'Reilly Media. Kindle Edition.]

type Done <-chan interface{}

func repeatFn(done Done, fn func() interface{}) <-chan interface{} {

valueStream := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

defer close(valueStream)

for {

select {

case <-done:

return

case valueStream <- fn():

}

}

}()

return valueStream

}

func take(done Done, valueStream <-chan interface{}, num int) <-chan interface{} {

takeStream := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

defer close(takeStream)

for i := 0; i < num; i++ {

select {

case <-done:

return

case takeStream <- <-valueStream:

}

}

}()

return takeStream

}

func main() {

done := make(chan interface{})

defer close(done)

rand := func() interface{} { return rand.Int() }

for num := range take(done, repeatFn(done, rand), 10) {

fmt.Println(num)

}

}

pipelineについてはgolang.orgのblogにも記事がありました。

Fan-Out, Fan-In

type Done <-chan interface{}

func repeatFn(done Done, fn func() interface{}) <-chan interface{} {

valueStream := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

defer close(valueStream)

for {

select {

case <-done:

return

case valueStream <- fn():

}

}

}()

return valueStream

}

func take(done Done, valueStream <-chan interface{}, num int) <-chan interface{} {

takeStream := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

defer close(takeStream)

for i := 0; i < num; i++ {

select {

case <-done:

return

case takeStream <- <-valueStream:

}

}

}()

return takeStream

}

func toInt(done Done, valueStream <-chan interface{}) <-chan int {

intStream := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(intStream)

for v := range valueStream {

select {

case <-done:

return

case intStream <- v.(int):

}

}

}()

return intStream

}

func primeFinder(done Done, intStream <-chan int) <-chan interface{} {

isPrime := func(n int) bool {

for i := 2; i < n; i++ {

if n%i == 0 {

return false

}

}

return n > 1

}

primeStream := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

defer close(primeStream)

for n := range intStream {

if isPrime(n) {

select {

case <-done:

return

case primeStream <- n:

}

} else {

select {

case <-done:

return

default:

}

}

}

}()

return primeStream

}

func fanIn(done Done, channels ...<-chan interface{}) <-chan interface{} {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

multiplexedStream := make(chan interface{})

multiplex := func(c <-chan interface{}) {

defer wg.Done()

for i := range c {

select {

case <-done:

return

case multiplexedStream <- i:

}

}

}

wg.Add(len(channels))

for _, c := range channels {

go multiplex(c)

}

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(multiplexedStream)

}()

return multiplexedStream

}

func main() {

done := make(chan interface{})

defer close(done)

start := time.Now()

rand := func() interface{} { return rand.Intn(500000000) }

randIntStream := toInt(done, repeatFn(done, rand))

finders := make([]<-chan interface{}, runtime.NumCPU())

fmt.Println("primes:")

for i := 0; i < len(finders); i++ {

finders[i] = primeFinder(done, randIntStream)

}

for prime := range take(done, fanIn(done, finders...), 10) {

fmt.Printf("\t%d\n", prime)

}

fmt.Printf("Search took: %v", time.Since(start))

}

実行結果:

primes:

98090563

129458047

277341737

183653891

276971353

427131847

88763767

228547051

339189757

379648553

Search took: 10.917536206s

処理をpipelineに落とし込めると、fan-in, fan-outを利用して、複数のgoroutineに処理を切り出せる。ただし、処理の順序が重要な場合はそう単純にはいかない。

The or-done channel

At times you will be working with channels from disparate parts of your

system. Unlike with pipelines, you can't make any assertions about how a

channel will behave when code you're working with is canceled via its

done channel. That is to say, you don't know if the fact that your

goroutine was canceled means the channel you're reading from will have

been canceled.

[Cox-Buday, Katherine. Concurrency in Go: Tools and Techniques for

Developers (p. 119). O'Reilly Media. Kindle Edition.]

loop:

for {

select {

case <-done:

break loop

case maybeVal, ok := myChan:

if ok == false {

return

}

// Do something with val

}

}

のようにindentが深くなってしまうので

func orDone(done <-chan interface{}, c <-chan interface{}) <-chan interface{} {

valStream := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

defer close(valStream)

for {

select {

case <-done:

return

case v, ok := <-c:

if ok == false {

return

}

select {

case valStream <- v:

case <-done:

}

}

}

}()

return valStream

}

for val := range orDone(done, myChan) {

// Do something with val

}

つねにchannelがblockされることを考慮して、done channelをcheckしないといけない点が参考になりました。。

The tee-channel

func tee(done <-chan interface{}, in <-chan interface{}) (_, _ <-chan interface{}) {

out1 := make(chan interface{})

out2 := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

defer close(out1)

defer close(out2)

for val := range orDone(done, in) {

var out1, out2 = out1, out2

for i := 0; i < 2; i++ {

select {

case <-done:

case out1 <- val:

out1 = nil

case out2 <- val:

out2 = nil

}

}

}

}()

return out1, out2

}

func main() {

done := make(chan interface{})

defer close(done)

out1, out2 := tee(done, take(done, repeat(done, 1, 2), 4))

for val1 := range out1 {

fmt.Printf("out1: %v, out2: %v\n", val1, <-out2)

}

}

結局, channelの内容をspewやppでdebugしていたので、最初から teeのようにしてlogにかけるようにするのはとても参考になりました。

The bridge-channel

func bridge(done <-chan interface{}, chanStream <-chan <-chan interface{}) <-chan interface{} {

valStream := make(chan interface{})

go func() {

defer close(valStream)

for {

var stream <-chan interface{}

select {

case maybeStream, ok := <-chanStream:

if ok == false {

return

}

stream = maybeStream

case <-done:

return

}

for val := range orDone(done, stream) {

select {

case valStream <- val:

case <-done:

}

}

}

}()

return valStream

}

func main() {

genVals := func() <-chan <-chan interface{} {

chanStream := make(chan (<-chan interface{}))

go func() {

defer close(chanStream)

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

stream := make(chan interface{}, 1)

stream <- i

close(stream)

chanStream <- stream

}

}()

return chanStream

}

for v := range bridge(nil, genVals()) {

fmt.Printf("%v ", v)

}

}

実行結果:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

channelのchannelを valueのchannelにするpattern.

channelのchannelはまだ書いたことがないので、書けるようになりたいですが、いまのところどういうところで使うのかわかっていません。使用例ご存知の方いらっしゃいましたら、教えてください。

headbeat

func doWork(done <-chan interface{}, pulseInterval time.Duration) (<-chan interface{}, <-chan time.Time) {

headbeat := make(chan interface{})

results := make(chan time.Time)

go func() {

defer close(headbeat)

defer close(results)

pulse := time.Tick(pulseInterval)

workGen := time.Tick(2 * pulseInterval)

sendPulse := func() {

select {

case headbeat <- struct{}{}:

default:

}

}

sendResult := func(r time.Time) {

for {

select {

case <-done:

return

case <-pulse:

sendPulse()

case results <- r:

return

}

}

}

for {

select {

case <-done:

return

case <-pulse:

sendPulse()

case r := <-workGen:

sendResult(r)

}

}

}()

return headbeat, results

}

func main() {

done := make(chan interface{})

time.AfterFunc(10*time.Second, func() { close(done) })

const timeout = 2 * time.Second

headbeat, results := doWork(done, timeout/2)

for {

select {

case _, ok := <-headbeat:

if ok == false {

return

}

fmt.Println("pulse")

case r, ok := <-results:

if ok == false {

return

}

fmt.Printf("results: %v\n", r.Second())

case <-time.After(timeout):

fmt.Println("worker goroutine is not healthy")

return

}

}

}

信頼できるものにしようと思ったら、死活監視は避けては通れないので、参考にしたいです。

Replicated Request

func doWork(done <-chan interface{}, id int, wg *sync.WaitGroup, result chan<- int) {

started := time.Now()

defer wg.Done()

simulatedLoadTime := time.Duration(1+rand.Intn(5)) * time.Second

select {

case <-done:

case <-time.After(simulatedLoadTime):

}

select {

case <-done:

case result <- id:

}

took := time.Since(started)

if took < simulatedLoadTime {

took = simulatedLoadTime

}

fmt.Printf("%v took %v\n", id, took)

}

func main() {

done := make(chan interface{})

result := make(chan int)

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(10)

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

go doWork(done, i, &wg, result)

}

firstReturned := <-result

close(done)

wg.Wait()

fmt.Printf("received an answer from #%v\n", firstReturned)

}

実行結果:

2 took 1.005156915s

9 took 2s

5 took 3s

3 took 2s

0 took 2s

6 took 4s

1 took 3s

8 took 1.005358415s

7 took 5s

4 took 1.005362998s

received an answer from #2

Rate Limiting

type RateLimiter interface {

Wait(context.Context) error

Limit() rate.Limit

}

func MultiLimiter(limiters ...RateLimiter) *multiLimiter {

byLimit := func(i, j int) bool {

return limiters[i].Limit() < limiters[j].Limit()

}

sort.Slice(limiters, byLimit)

return &multiLimiter{limiters: limiters}

}

type multiLimiter struct {

limiters []RateLimiter

}

func (l *multiLimiter) Wait(ctx context.Context) error {

for _, l := range l.limiters {

if err := l.Wait(ctx); err != nil {

return err

}

}

return nil

}

func (l *multiLimiter) Limit() rate.Limit {

return l.limiters[0].Limit()

}

func Per(eventCount int, duration time.Duration) rate.Limit {

return rate.Every(duration / time.Duration(eventCount))

}

func Open() *APIConnection {

return &APIConnection{

apiLimit: MultiLimiter(

rate.NewLimiter(Per(2, time.Second), 2),

rate.NewLimiter(Per(10, time.Minute), 10),

),

diskLimit: MultiLimiter(

rate.NewLimiter(rate.Limit(1), 1),

),

networkLimit: MultiLimiter(

rate.NewLimiter(Per(3, time.Second), 3),

),

}

}

type APIConnection struct {

networkLimit,

diskLimit,

apiLimit RateLimiter

}

func (a *APIConnection) ReadFile(ctx context.Context) error {

err := MultiLimiter(a.apiLimit, a.diskLimit).Wait(ctx)

if err != nil {

return err

}

return nil

}

func (a *APIConnection) ResolveAddress(ctx context.Context) error {

err := MultiLimiter(a.apiLimit, a.networkLimit).Wait(ctx)

if err != nil {

return err

}

return nil

}

func main() {

defer log.Printf("Done")

log.SetOutput(os.Stdout)

log.SetFlags(log.Ltime | log.LUTC)

APIConnection := Open()

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(20)

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

err := APIConnection.ReadFile(context.Background())

if err != nil {

log.Printf("cannot ReadFile: %v", err)

}

log.Printf("ReadFile")

}()

}

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

err := APIConnection.ResolveAddress(context.Background())

if err != nil {

log.Printf("cannot ResolveAddress: %v", err)

}

log.Printf("ResolveAddress")

}()

}

wg.Wait()

}

実行結果::

16:00:16 ResolveAddress

16:00:16 ReadFile

16:00:17 ReadFile

16:00:17 ResolveAddress

16:00:18 ReadFile

16:00:18 ResolveAddress

16:00:19 ReadFile

16:00:19 ResolveAddress

16:00:20 ReadFile

16:00:20 ResolveAddress

16:00:22 ResolveAddress

16:00:28 ResolveAddress

16:00:34 ResolveAddress

16:00:40 ReadFile

16:00:46 ReadFile

16:00:52 ReadFile

16:00:58 ReadFile

16:01:04 ResolveAddress

16:01:10 ReadFile

16:01:16 ResolveAddress

16:01:16 Done

golang.org/x/time/rate を利用.

rateのlimitはかならず登場する要素だと思うのでしっかり実装できるようになりたい

context package

context packageについても説明がありましたが、割愛.

doneを渡すところは 基本的にcontext.Contextを渡すようにしたほうがよいので、基本的にはもうdoneはつかわなくなると思いました。

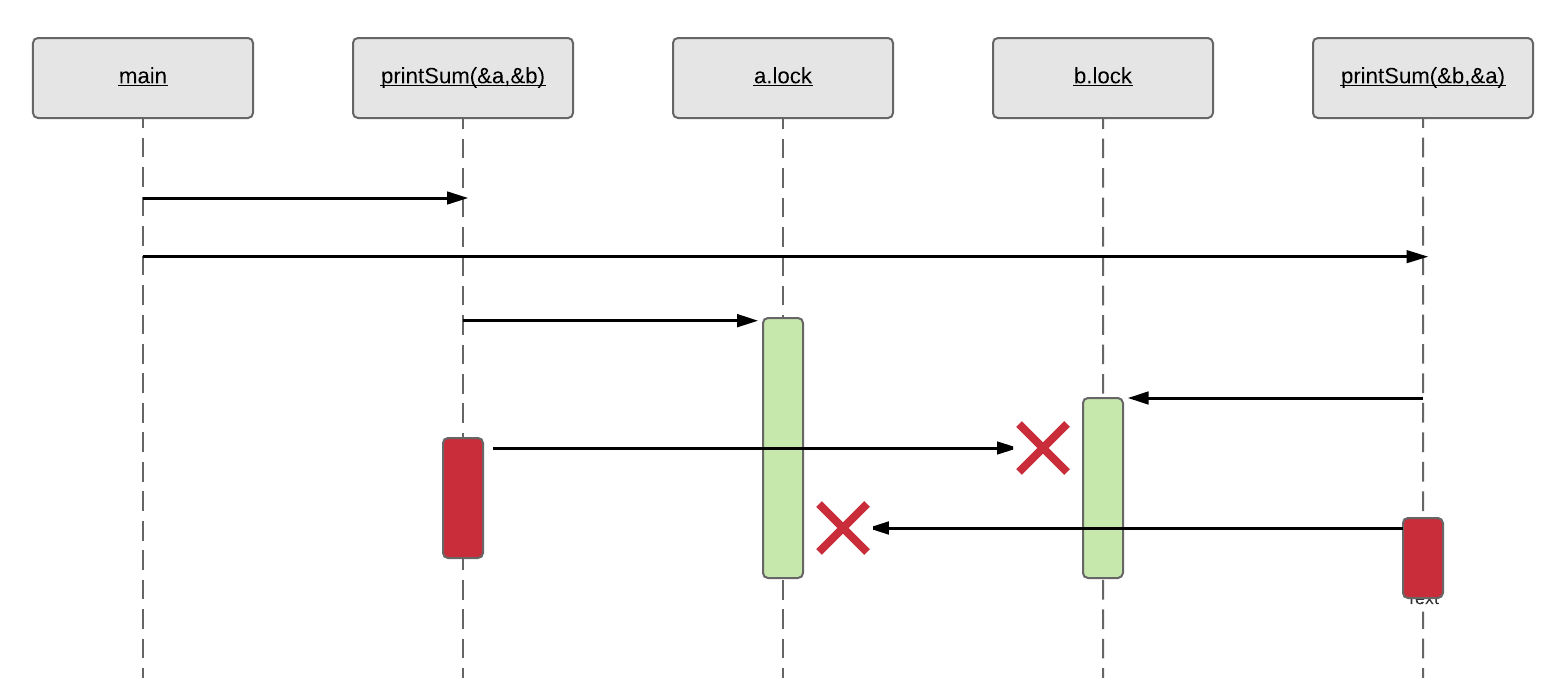

Deadlocks, Livelocks, and Starvation

Deadlock

type value struct {

mu sync.Mutex

value int

}

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

printSum := func(v1, v2 *value) {

defer wg.Done()

v1.mu.Lock()

defer v1.mu.Unlock()

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

v2.mu.Lock()

defer v2.mu.Unlock()

fmt.Printf("sum=%v\n", v1.value+v2.value)

}

var a, b value

wg.Add(2)

go printSum(&a, &b)

go printSum(&b, &a)

wg.Wait()

}

実行すると:

go run main.go

fatal error: all goroutines are asleep - deadlock!

sequence図

Deadlockがおきる条件

Coffman COnditionsとして知られているらしいです

-

Mutual Exclusion

- A concurrent process holds exclusive rights to resource at any one time.

-

Wait For Condition

- A concurrent process must simultaneously hold a resource and be

waiting for an additional resource

- A concurrent process must simultaneously hold a resource and be

-

No Preemption (Preemption: 先買(権), 先取り)

- A resource held by a concurrent process can only be released by that

process

- A resource held by a concurrent process can only be released by that

-

Circular Wait

- A concurrent process(P1) must be waiting on a chain of other concurrent processes(P2), which are in turn waiting on it(P1)

この条件に, さきほどのsample codeをあてはめてみると

-

printSumfunctionはvalue a, bに exclusive rightを

requireしているので、当てはまる -

printSumはa,bをholdして、他方をwaitしているので,当てはまる - goroutineにvalueをreleaseさせることができないので、当てはまる

- 2つの

printSumは互いに、相手を待機しているので当てはまる

Livelock

Livelocks are programs that are actively performing concurrent

operations, but these operations do nothing to move the state of the

program forward.

[Cox-Buday, Katherine. Concurrency in Go: Tools and Techniques for

Developers (p. 13). O'Reilly Media. Kindle Edition.]

二人の人物が道で対面して、お互いに同じ方向に移動しようとしてしているのを表している

func main() {

cadence := sync.NewCond(&sync.Mutex{})

go func() {

for range time.Tick(1 * time.Millisecond) {

cadence.Broadcast()

}

}()

takeStep := func() {

cadence.L.Lock()

cadence.Wait()

cadence.L.Unlock()

}

tryDir := func(dirName string, dir *int32, out *bytes.Buffer) bool {

fmt.Fprintf(out, " %v", dirName)

// directionに一歩進む

atomic.AddInt32(dir, 1)

// 同じrateで動く

takeStep()

if atomic.LoadInt32(dir) == 1 {

fmt.Fprint(out, ". Success!")

return true

}

takeStep()

// 進もうとしたdirectionに進めなかったので諦めて戻る

atomic.AddInt32(dir, -1)

return false

}

var left, right int32

tryLeft := func(out *bytes.Buffer) bool { return tryDir("left", &left, out) }

tryRight := func(out *bytes.Buffer) bool { return tryDir("right", &right, out) }

walk := func(walking *sync.WaitGroup, name string) {

var out bytes.Buffer

defer func() { fmt.Println(out.String()) }()

defer walking.Done()

fmt.Fprintf(&out, "%v is trying to scoot:", name)

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

if tryLeft(&out) || tryRight(&out) {

return

}

}

fmt.Fprintf(&out, "\n%v tosses her hands up in exasperation!", name)

}

var peopleInHallway sync.WaitGroup

peopleInHallway.Add(2)

go walk(&peopleInHallway, "Alice")

go walk(&peopleInHallway, "Barbara")

peopleInHallway.Wait()

}

実行結果:

Alice is trying to scoot: left right left right left right left right left right

Alice tosses her hands up in exasperation!

Barbara is trying to scoot: left right left right left right left right left right

Barbara tosses her hands up in exasperation!

Starvation

Starvation is any situation where a concurrent process cannot get all

the resources it needs to perform work. Cox-Buday, Katherine.

[Concurrency in Go: Tools and Techniques for Developers (p. 16).

O'Reilly Media. Kindle Edition.]

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

var sharedLock sync.Mutex

const runtime = 1 * time.Second

greedyWorker := func() {

defer wg.Done()

var count int

for begin := time.Now(); time.Since(begin) <= runtime; {

sharedLock.Lock()

time.Sleep(3 * time.Nanosecond)

sharedLock.Unlock()

count++

}

fmt.Printf("Greedy worker was able to execute %v work loops\n", count)

}

politeWorker := func() {

defer wg.Done()

var count int

for begin := time.Now(); time.Since(begin) <= runtime; {

sharedLock.Lock()

time.Sleep(1 * time.Nanosecond)

sharedLock.Unlock()

sharedLock.Lock()

time.Sleep(1 * time.Nanosecond)

sharedLock.Unlock()

sharedLock.Lock()

time.Sleep(1 * time.Nanosecond)

sharedLock.Unlock()

count++

}

fmt.Printf("Polite worker was able to execute %v work loops\n", count)

}

wg.Add(2)

go greedyWorker()

go politeWorker()

wg.Wait()

}

実行結果:

Polite worker was able to execute 388028 work loops

Greedy worker was able to execute 884950 work loops

Goroutines and the Go runtime

第6章のテーマ.ほとんど理解できませんでした

感想

concurrentの定義がのっていたので、その点だけでも買ってよかったです。

channelやgoroutine, sync package等の説明やsample codeが豊富で、concurrency関連の様々な内容を網羅的に説明してくれていたので、blogやらでいろいろ調べていたものが整理できてよかったです。

英語力や、softwareの開発経験のなさで理解できないところも多々あり、ここでのメモは本書のほんの一部です。