This is a memorandum to remind myself how the code of arbitrary gaussian distribution generation works.

To generate multiple gaussian distributions, it's a good idea to employ trigonometric functions.

from math import cos, sin

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# prepare variables

label = 1 # index of an individual distribution

n_labels = 6 # total number of distributions

x = np.random.normal(0, 1, (1000,1)) # x coord. of random numbers

y = np.random.normal(0, 1, (1000,1)) # y coord. of random numbers

# define the angle for each distribution

r = 2.0 * np.pi / float(n_labels) * float(label)

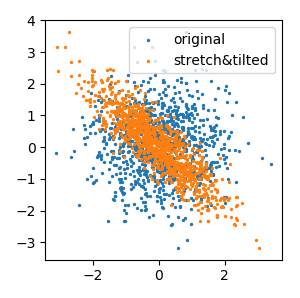

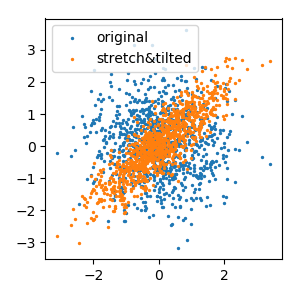

To stretch and tile the distribution, you can do this:

new_x = x * cos(r) - y * sin(r)

plt.figure(figsize=(3, 3))

plt.scatter(x, y, s=2)

plt.scatter(new_x, y, s=2)

plt.legend(['original', 'stretch&tilted'])

plt.show()

then, you'll get following result:

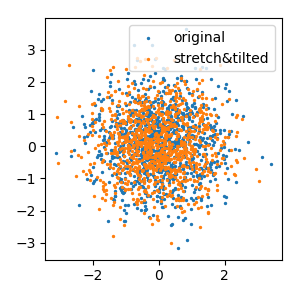

You can do the same to y coordinate as well.

new_y = x * sin(r) + y * cos(r)

plt.figure(figsize=(3, 3))

plt.scatter(x, y, s=2)

plt.scatter(x, new_y, s=2)

plt.legend(['original', 'stretch&tilted'])

plt.show()

If you use both new_x and new_y, the distribution will be a normal one.

plt.figure(figsize=(3, 3))

plt.scatter(x, y, s=2)

plt.scatter(new_x, new_y, s=2)

plt.legend(['original', 'stretch&tilted'])

plt.show()

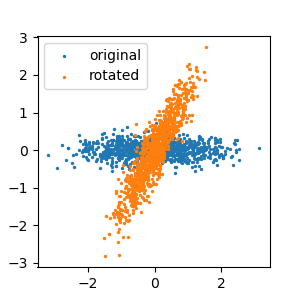

This is useful when the standard deviations of the distribution in x and y coordinates are different.

x1 = np.random.normal(0, 1, (1000,1))

y1 = np.random.normal(0, 0.2, (1000,1))

new_x1 = x1 * cos(r) - y1 * sin(r)

new_y1 = x1 * sin(r) + y1 * cos(r)

plt.figure(figsize=(3, 3))

plt.scatter(x1, y1, s=2)

plt.scatter(new_x1, new_y1, s=2)

plt.legend(['original', 'rotated'])

plt.show()

You can add some shift to the whole distribution towards a certain direction defined by r that we have defined previously.

shift = 2 # the amount of shift

new_x += shift * cos(r) # parallel shift to the direction of r

new_y += shift * sin(r) # parallel shift to the direction of r

You can make it as a function for convenience.

def sample(x, y, label, n_labels, shift):

r = 2.0 * np.pi / float(n_labels) * float(label)

new_x = x * cos(r) - y * sin(r) # change the slope of the distribution

new_y = x * sin(r) + y * cos(r) # change the slope of the distribution

new_x += shift * cos(r) # parallel shift to the direction of r

new_y += shift * sin(r) # parallel shift to the direction of r

return np.concatenate((new_x, new_y), axis=1)

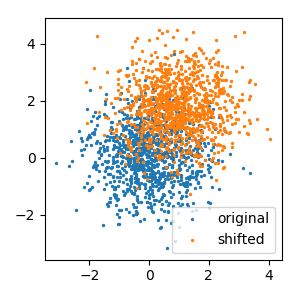

new_xy = sample(x,y,1,6,2)

plt.figure(figsize=(3,3))

plt.scatter(x,y,s=2)

plt.scatter(new_xy[:,0],new_xy[:,1],s=2)

plt.legend(['original','shifted'])

plt.show()

plt.tight_layout()

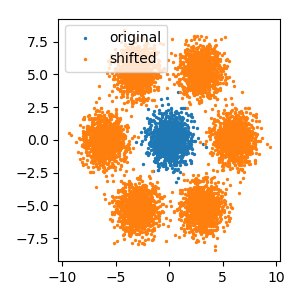

Let's make a circle of 6 gaussian distributions!

n_labels = 6

new_xy = np.empty((0,2))

for i in range(n_labels):

a = sample(x, y, i+1, n_labels, 6)

new_xy = np.concatenate((new_xy, a), axis=0)

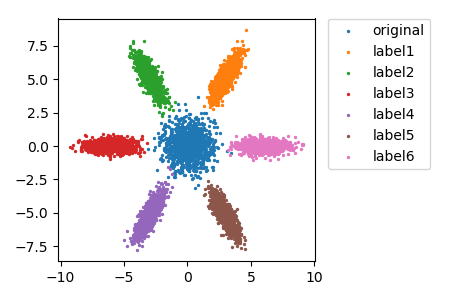

We can also give each distribution a different label

n_labels = 6

plt.figure(figsize=(4.5, 3))

plt.scatter(x, y, s=2, label='original')

for i in range(n_labels):

x1 = np.random.normal(0, 1, (1000,1))

y1 = np.random.normal(0, 0.3, (1000,1))

new_xy = sample(x1, y1, i+1, n_labels, 6)

plt.scatter(new_xy[:,0], new_xy[:,1],

s=2, label='label{}'.format(i+1))

plt.legend(bbox_to_anchor=(1.05, 1),

loc='upper left', borderaxespad=0)

plt.show()

plt.tight_layout()