はじめに

『ベイジアンな脳:予測処理モデル』脳をベイズ理論的に説明できるという

面白そうな記事を見つけたので、

意訳の練習がてら紹介したいと思います。

元記事(英文):The Bayesian Brain: An Introduction to Predictive Processing

※間違い指摘くださると有難いです。直します。

![]()

![]() では早速

では早速 ![]()

![]()

The Bayesian Brain: An Introduction to Predictive Processing ベイジアンな脳〜予測処理モデル

THE GREATEST THEORY OF ALL TIME?

The more I learn about the Bayesian brain, the more it seems to me that the theory of predictive processing is about as important for neuroscience as the theory of evolution is for biology, and that Bayes’ law is about as important for cognitive science as the Schrödinger equation is for physics.

That is quite an ambitious statement: if our brains really are Bayesian, which is to say that predictive processing is the fundamental principle of cognition, it would mean that all our sensing, feeling, thinking, and doing is a matter of making predictions.

In this blog post, I won’t discuss the ample evidence we have for this theory,1 but limit myself to presenting the idea itself. Though it is probably not the greatest theory of all time, it does have the potential to become the greatest theory in the history of cognitive science.

史上最強といっても過言ではないベイズ脳理論

ベイズ脳理論は、神経科学においてとても重要なものになるだろう。

いうなれば、生物学にとっての進化論、

認知科学にとってのベイズ定理、物理学にとってのシュレディンガー方程式くらいに、それはもうとってもとっても重要なのである。

ちょっと煽り厨っぽくいうと

脳がベイズ理論に基づいているというなら、人が持つ感覚や思考や行動などのあらゆる全ての行為が、この予測処理に基づく問題ということになる。

このブログでは、理論それ自体にどのくらい信憑性があるかどうかを検証しない。代わりに概要を説明する。

もちろん、この理論が脳のはたらきの全てを説明することはできないけど

認知科学の歴史においての重大な理論となりうることを伝えたい。

WHAT IS PREDICTIVE PROCESSING?

During every moment of your life, your brain gathers statistics to adapt its model of the world, and this model’s only job is to generate predictions. Your brain is a prediction machine. Just as the heart’s main function is to pump blood through the body, so the brain’s main function is to make predictions about the body. For example, your brain predicts incoming sensory data: what you’re about to perceive from within (interoception) as from without (exteroception).

We used to think that perception is a simple feed-forward process. Say, you open your eyes and sensory data travels from your retina into your brain where it is fed forward through multiple levels of cortical processing, ultimately leading to a motor reaction. If your brain is Bayesian, however, it doesn’t process sensory data like that. Instead, it uses predictive processing (also known as predictive coding)2 to predict what your eyes will see before you get the actual data from the retina.

Your brain runs an internal model of the causal order of world that continually creates predictions about what you expect to perceive. These predictions are then matched with what you actually perceive, and the divergence between predicted sensory data and actual sensory data yields a prediction error. The better a prediction, the better the fit, and the less prediction error propagates up the hierarchy. Wait, what’s a hierarchy?

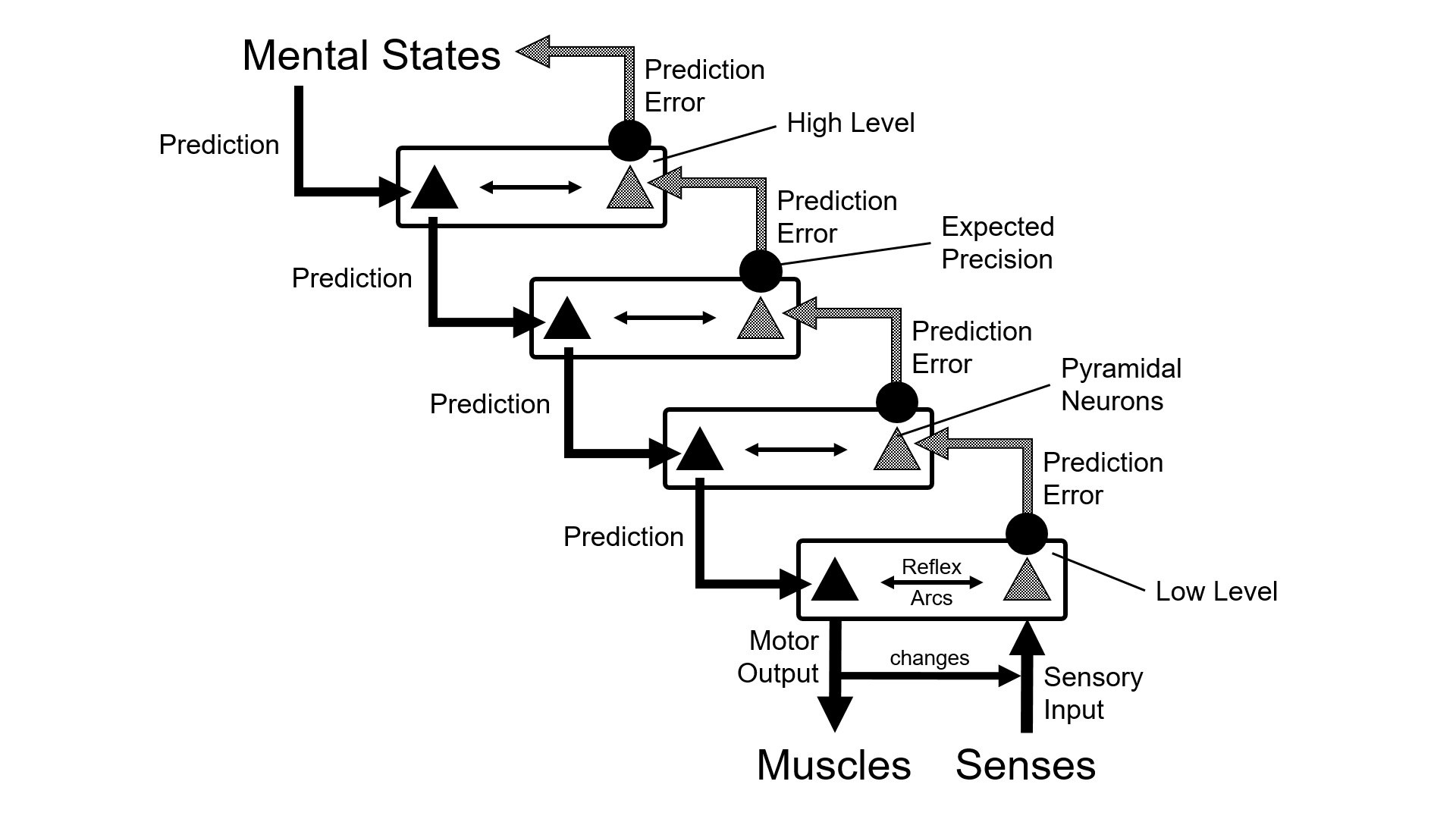

Your internal model (also called generative model because it generates predictions) is structured as a bidirectional hierarchical cascade:

The model is a cascade because it involves multiple levels of processing, multiple cortical areas in the brain.

The model is hierarchical because it comprises higher and lower processing layers: lower levels process simple data (e.g., sensory stimuli, affective signals, motor commands), higher level process categorizations (e.g., object recognition, emotion classification, action selection), and the highest levels process mental states (e.g., mental imagery, emotion experience, conscious goals, planning, reasoning).3

The model is bidirectional because signals continually propagate in both directions: predictions move downward to pyramidal neurons of lower levels while prediction errors move upward to pyramidal neurons of higher levels.

Each processing layer predicts what’s happening at the layer below and receives an error signal from that lower layer—a dynamic process that may or may not loop all the way down to incoming sensory data. A model is successful when the predictions it generates at every layer of the hierarchical cascade are accurate, producing only minimal prediction errors.

If your predictions don’t fit the actual data, you get a high prediction error that updates your internal model—to reduce further discrepancies between expectation and evidence, between model and reality. Your brain hates unfulfilled expectations, so it structures its model of the world and motivates action in such a way that more of its predictions come truer. Here’s a schematic diagram of how this all works:

predictive processing

Schematic depiction of a bidirectional hierarchical cascade.

The black circles in the diagram (at the prediction error sources) depict something I haven’t explained yet, namely expected precisions. Precisions determine the weight of prediction errors. If your brain expects that a certain prediction error won’t be particularly reliable or important, it decreases its weight and thus the extent to which the error can update your internal model. For example, if it’s dark and foggy outside, you can’t expect the visual information you receive to be particularly reliable, so you add that expectation—in the form of expected precisions that modulate error signals—to your predictions in order to prevent your model from being unduly distorted by unreliable data. In other words, precisions are a measure of uncertainty that expresses your brain’s trust in the expected sensory data and the ensuing the error signals. The brain wants prediction errors to have a high signal-to-noise ratio.

Expected precisions are formally equivalent to inverse variance and functionally equivalent to attention. When you pay a lot of attention to an object, you become confident that the information you get from it is relatively accurate. Say, you’ve been mindfully looking at a Ferrari under good lighting conditions, so you’re pretty confident that it is red. The more attentive you are, the more weight you put on potential error signals. By contrast, if you’re not really focused, your brain turns down the “error volume,” i.e., the impact a prediction error can have on your model.

そもそも予測処理って何?

日々の生活の中で、人の脳は、統計データを集めて、世界のモデルに適用している。この独自の世界のモデルを何につかうかというと、それはただ一つ、予測することに使われるのだ。君の脳は、予測マシンなのだ。心臓の主なる役割が、身体中に血液を送るポンプ機能のように、脳の主な役割は、自分の体に関する予測することなのだ。

脳は、体の内側や外側から、次の瞬間に何が認知(検知)されるのか、あらかじめ予測している。

かつては『認知』というと、

単純な「入力(刺激)と出力(反応)」のプロセスだと考えられていた。

目から入った光は網膜を通って、脳のいくつかの処理を経て、何かしらの行動、反応が起きる、というような考え方が主流だった。

しかしながら、脳ベイズ理論的には、上記のような考え方はしない。

ベイジアン脳モデルでは、単純な入力と出力ではなく、脳では予測処理が行われると考える。

入力(刺激)をあらかじめ予測し、実際に光が網膜に入ってくる前に、モノを見るということになる。

人の脳内には、次の瞬間に何を認知するかをリアルタイムで予測し形作られた世界モデルが存在している、と言える。そして脳内で予測していたことと実際に起きたことを答え合わせが常に行われている。

予測データと実際の検知データに逸脱があれば、それは予測エラーとなる。予測エラーが少なく良い予測ができるほど、それは予測モデルに適用されていく。

それはヒエラルキの型を生み出すことにつながる。

ここで言うヒエラルキについて説明する。

予測モデルは、**バイディレクショナル・ヒエラルキカル・カスケード(bidirectional hierarchical cascade)**の構造をしている。

・モデルはカスケード(滝・階段)型である。なぜなら脳内の複数の皮質野で行われる複数の処理が含まれるからだ。

・モデルはヒエラルキ型(階層型)である。なぜなら、高階層から低階層の処理レイヤーで成り立っているからだ。低階層では、刺激や運動司令などのシンプルなデータ処理が行われ、高階層では、物体判別、感情分類、行動選択などの、カテゴリー処理が行われる。

そして最上階では、感情の状態(例えば心理描写、感情の経験、目的意識、計画、理由づけ)の処理が行われる。

・モデルはバイディレクショナルである。なぜなら信号は両方向で伝搬されるからである。予測が、低階層の錐体細胞に向かって伝搬されながら、予測エラーは高階層の錐体細胞に向かって伝搬される。

これらの各層は一つ下の階層からエラー信号を受信する。動的なプロセスはループしたりしなかったりしながら、検知されるデータに向けて落とされて行く。

ヒエラルキカスケードの全ての階層生成される予測が、正しく、エラーが最小であった場合に、モデルは成功したことになる。

もし、あなたの予測が実際に起こったこととマッチしなかった場合、それは重大な予測エラーが発生したことになり、期待と現実の不一致が減少されるように、あなたのモデルが修正されることとなる。

黒点(予測エラーの部分にある)は、予測の精度を表す。(↑図)

この精度は、予測エラーの重みを決定する。

もし、あなたの脳が、ある特定の予測エラーに関しては、重要な問題ではない、もしくは信頼に値しないと判断した場合は、重みを調整(軽く)し、そのようにモデルを更新する。例えば、、外が暗くて霧がかかっていたとすると、あなたは自分の視覚情報をそこまで信頼できないと判断して、他の予測をするだろう。「見えない」という予測エラーが発生しても、そのエラー信号を調整するであろう。言い換えれば、精度というのは、脳が信じてしまう予測データや予測エラーそのものの不正確さを測りであるといえる。

脳は、高い信号対雑音比を把握するために、予測エラーが欲しいのである。

(続く)