Introduction

Mental Poker is a protocol that allows us a fair poker game without any fair third-party1 over the phone or the Internet. If there are some malicious players among the participants of the poker game, they can do some cheats, for example, they will pretend to take cards which they want, or to open cards that they have not drawn. Mental Poker is a novel and traditional protocol that can prevent us from these cheats and protect a secret such as players hand from others, even though there is no fair third-party.

Mental Poker was discovered in 1981 by Shamir, Rivest and Adleman who invented RSA cryptography2, and its research has been continued recently. Using the three operations: shuffle, draw and open the hand, which are required for playing poker, other games like Mahjong can be played by the same way. So we think that Mental Poker provides fairer games.

However, we did not know whether we could play more complicate games like Werewolf (Mafia) using Mental Poker or not. Werewolf is a game that divides players into two groups, werewolves and villagers, and then Villagers can not distinguish whether the other players are werewolves or villagers, while werewolves can distinguish all players are werewolves or villagers. It seemed impossible to execute such a flexible grouping without a fair third-party. But recently, a paper that says the grouping like this can be done was submitted. So I consider Werewolf can be played using Mental Poker.

In this article, I will first explain about an intuitive Mental Poker protocol, next introduce permutations, and then discuss secure groping protocol with number cards and voting, finally I will talk about making up a fair Werewolf game without a moderator3.

Intuitive Mental Poker

In this section, I will make a Mental Poker protocol with physical tools like boxes and padlocks. If you would like to lean about mathematical methods of Mental Poker, you can read references.

Boxes and Padlocks

We see the way how Alice and Bob in remote place can do three operations, shuffle, draw and open without any cheats using boxes and padlocks.

In this section, the box is a container that does not see at all what is contained from the outside. You can put any number of padlocks on the box. If there is only the padlock that is put by you, you can remove the padlock using your key and you can see the content inside the box, but you cannot open the box where one or more of the other's padlocks are put.

For the sake of simplicity we assume that only two people, Alice and Bob, will run the protocol.

Shuffle

We shuffle the $n$ cards using boxes and padlocks as follows.

- Alice puts cards one by one into a box, then shuffles the boxes after put padlocks $A_O$ on every box

- Alice sends all boxes to Bob using courier etc.

- Bob shuffles the boxes

- Bob puts his padlocks $B_i$ on each box $i$, one by one

- Bob sends all boxes to Alice

- Alice removes padlocks $A_O$ from all boxes

- Alice puts her padlocks $A_i$ one by one on each box $i$

In (2), Bob is unable to open any box because they sent to him are locked with Alice's padlocks. Even if Alice arranges the boxes in her intentional order, it does not makes sense because Bob shuffles the boxes in (3). In addition, Bob can not see the content inside any box because they are locked by Alice, even if he arranges the boxes in his intentional order, it makes no sense.

Also, Alice puts padlocks $A_O$ on the box in (1), then sends them to Bob, and removes them in (6). If Alice puts the other padlocks on the box from the beginning, she can make a correspondence table of the card in the box. The reason why even if Bob puts padlock on the boxes, Alice can identify the contents of the box depending on which padlock can be removed. It loses fairness, so in order to avoid this, Alice must put the padlocks on the boxes twice in total.

Draw

Next we will consider is draw. We think that Alice will draw one card from the deck4. At the end of the shuffle, we assume that Alice has the deck.

- Alice picks one box $i$ from the deck and teaches the number $i$ to Bob

- Bob sends Alice the key of the padlock $B_i$ that was put on box $i$

- Alice removes the padlock $B_i$ using the key received from Bob in (2)

- Alice removes her padlock $A_i$ from the box $i$ and gets the card inside the box $i$

By doing this, Alice can draw a card without being known it by Bob.

Open

When Alice would like to open the card to Bob, Alice just publishes the card to Bob.

Verification

In order to verify that there is no cheat, Alice and Bob will reveal all the keys of their padlocks and check the contents of all boxes. Also, if Alice and Bob have the hands, that will also be made open. If there is duplication or loss on the card, we know that someone did cheats.

Problems of Intuitive Mental Poker

Using the protocol, you can do the operations such as shuffle, draw and open but there are some problems.

First, in this protocol, players can verify that there is no cheat by opening all the boxes at the end and checking contents inside them. The players also reveal their hands, which can not help making their strategy clear. Therefore it is necessary to verify whether there are cheats or not without revealing players' hands. In addition, there is my article (Japanese) as an example of an implementation of Mental Poker in a mathematical way5.

Permutation

As a preparation before leaning secure grouping protocol, we consider permutations. Note that this section refered the article (Japanese).

Definition and Arithmetic

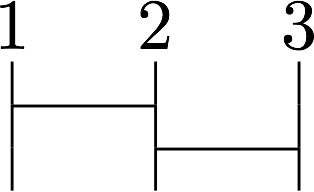

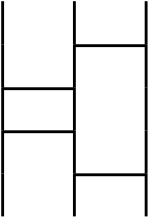

An intuitive explaination of a permutation is Amidakuji (Ghost Leg) as follows.

The above image means a parmutation that is $1 \rightarrow 3, 2 \rightarrow 1, 3 \rightarrow 2$. I will omit the number of the permutation image as follows.

Given a finite set $X := {1, 2, \dots, n}$, a bijective mapping $\sigma$ that maps an element $x \in X$ to $y \in X$ is called a $n$th order permutation. The permutation $1 \rightarrow i_1, 2 \rightarrow i_2, \dots n \rightarrow i_n$ is written as follows.

\left(

\begin{array}{cccc}

1 & 2 & \dots & n \\

i_1 & i_2 & \dots & i_n

\end{array}

\right)

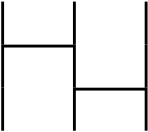

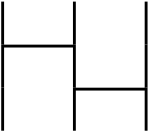

We consider two permutations like these.

We define a product of two permutations $\sigma * \rho$ as follows.

$$

(\sigma * \rho)(i) := \rho(\sigma(i))

$$

It means that $\sigma * \rho$ is permuting by $\sigma$ then permuting by $\rho$. So it makes the bellow image.

$\sigma * \rho$ is a permutation that is $1 \rightarrow 2, 2 \rightarrow 1, 3 \rightarrow 3$, it is bijective so $\sigma * \rho$ is also a permutation by the definition. The product of integers, for example, $5 \times 3$ equals to $3 \times 5$, which was changed the order. In the product of permutations, $\rho * \sigma$ that is changed the order from $\sigma * \rho$ is as follows.

This permutation is $1 \rightarrow 3, 2 \rightarrow 2, 3 \rightarrow 1$, does not equal to the $\sigma * \rho$. Thus, if we change the order of the product of permutations, it is the other permutation.

Identity Element

In the product of integer, the following is holds for any integer $x$.

$$

x \times 1 = 1 \times x = x

$$

An integer $1$ that does not change the original value after multiplied is called the identity element of the integer. Also there is the identity elements in permutations, for example, the following permutation is an identity element of the $3$rd order permutation.

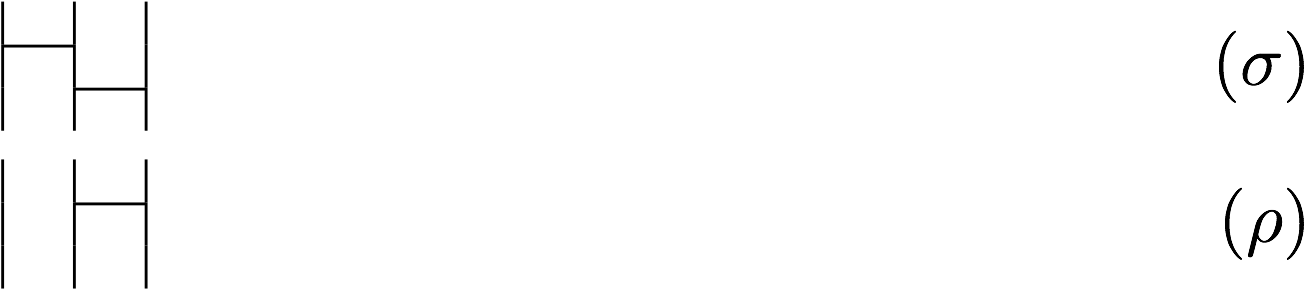

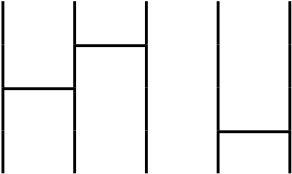

This is a permutation $1 \rightarrow 1, 2 \rightarrow 2, 3 \rightarrow 3$. For all $i \in X$, the permutation $e$ for that $e(i) = i$ holds is called an identity element of the $n$th order permutation. For example, we consider the product of the identity elemnet with the following permutation $\sigma$.

First $e * \sigma$ is as follows.

Next $\sigma * e$ is as follows.

Thus, both $e * \sigma$ and $\sigma * e$ equals to $\sigma$ so $e$ is an indentity element.

Inverse Element

In the product of integers, there is the inverse element $\frac{1}{x}$ for any integer $x$ and the following holds.

$$

x \times \frac{1}{x} = \frac{1}{x} \times x = 1

\def\Inv#1{#1^{-1}}

$$

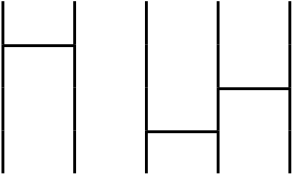

The product of an integer and its inverse element always equals to $1$ (identity element). Similarly for permutations, we can think a permutation that reverses the permutation. For example, $\sigma$ is the following permutation.

$\sigma$ is a permutation $1 \rightarrow 3, 2 \rightarrow 1, 3 \rightarrow 2$ so the reverse permutation $\rho$ that is $1 \rightarrow 2, 2 \rightarrow 3, 3 \rightarrow 1$ as follows.

$\sigma * \rho$ is as follows.

And $\rho * \sigma$ is as follows.

The both $\sigma * \rho$ and $\rho * \sigma$ is the permutation $1 \rightarrow 1, 2 \rightarrow 2, 3 \rightarrow 3$ so we can see they are identity elements. So $\rho$ that reverses $\sigma$ is called an inverse element of $\sigma$ and we can write $\Inv\sigma$ as the inverse element of $\sigma$. The following always holds true.

$$

\sigma * \Inv\sigma = \Inv\sigma * \sigma = e

$$

Cyclic Permutation

We consider the following permutation $\sigma$.

This permutation is $\sigma$ is $1 \rightarrow 3, 2 \rightarrow 1, 3 \rightarrow 2$ and this transfers the number cyclically like $1 \rightarrow 3 \rightarrow 2 \rightarrow 1 \rightarrow 3 \rightarrow 2 \cdots$. A permutation such a $\sigma$ is called a cyclic permutation and we write it as $(1, 3, 2)$. Strictly speaking, when a permutation $\sigma$ transfers the $k$ numbers $a_1, a_2, \dots, a_k, (1 \le k \le n)$ as long as $a_1$ is the minimum among $a_1, a_2, \dots, a_k$ to $\sigma(a_1) = a_2, \sigma(a_2) = a_3, \dots, \sigma(a_{n-1}) = a_n, \sigma(a_n) = a_1$ cyclically and it does not transfer other numbers, $\sigma$ is called a size $k$ cyclic permutation and it is written $(a_1, a_2, \dots, a_k)$. We consider a slightly larger permutation $\sigma$ such as the following.

This permutation can be expressed by the product of a cyclic permutation $(1, 2, 3)$ and a cyclic permutation $(4, 5)$. So we can write $\sigma$ as follows.

$$

\sigma = (1, 2, 3)(4, 5)

$$

An arbitrary permutation can be expressed by the product of cyclic permutation which does not contain the same number. Also, a cyclic permutation that does not contain the same number are called disjoint cyclic permutation.

Type

When a permutation $\tau$ is the product of some disjoint cyclic permutations, $\tau$ has a type $\left<r_1^{m_1}, r_2^{m_2}, \dots, r_k^{m_k}\right>$ where the number of size $r_i$ cyclic permutationfor is $m_i$ for each $i := 1, 2, \dots k$. For example, a permutation $\tau := (1, 2)(3, 4, 5)$ is as follows.

$\tau$ has the type $\left<2^1, 3^1\right>$.

Conjugated Permutation

For permutations $\tau$ and $\sigma$, $\Inv\sigma \tau \sigma$ is called conjugated permutation6. We consider what are the characteristics of conjugated permutations. For example, there are two permutations: $\tau := (1, 3, 2)$ and the the following permutation $\sigma$ where $i_1, i_2, i_3$ are choosen from $1, 2, 3$ as not to overlap.

\begin{align}

\sigma := \left(

\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

i_1 & i_2 & i_3

\end{array}

\right)

\end{align}

The conjugated permutation $\Inv\sigma \tau \sigma$ is as follows.

\begin{align}

\Inv{\left(

\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

i_1 & i_2 & i_3

\end{array}

\right)} (1, 3, 2) \left(

\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

i_1 & i_2 & i_3

\end{array}

\right) &= \left(

\begin{array}{ccc}

i_1 & i_2 & i_3 \\

1 & 2 & 3

\end{array}

\right) (1, 3, 2) \left(

\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

i_1 & i_2 & i_3

\end{array}

\right) \\

&= \left(

\begin{array}{ccc}

i_1 & i_2 & i_3 \\

1 & 2 & 3

\end{array}

\right)

\left(

\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

i_3 & i_1 & i_2

\end{array}

\right) \\

&= \left(

\begin{array}{ccc}

i_1 & i_2 & i_3 \\

i_3 & i_1 & i_2

\end{array}

\right) \\

&= (i_1, i_3, i_2)

\end{align}

The conjugated permutation $\Inv\sigma \tau \sigma$ is a permutation whose type equals to $\tau$ because $i_1, i_2, i_3$ are choosen from $1, 2, 3$ as not to overlap.

Next we consider $\Inv\sigma \tau^2 \sigma$ using $\tau^2 = \tau * \tau = (1, 2, 3)$.

\begin{align}

\Inv{\left(

\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

i_1 & i_2 & i_3

\end{array}

\right)} (1, 2, 3) \left(

\begin{array}{ccc}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

i_1 & i_2 & i_3

\end{array}

\right)

&= \left(

\begin{array}{ccc}

i_1 & i_2 & i_3 \\

i_2 & i_3 & i_1

\end{array}

\right) \\

&= (i_1, i_2, i_3)

\end{align}

If we fix the values of $i_1, i_2, i_3$, we get another cyclic permutation. Since $\tau^3 = \tau * \tau * \tau = e$, $\Inv\sigma \tau^3 \sigma$ equals to $e$. In the same way, $\Inv\sigma \tau^4 \sigma = \Inv\sigma \tau \sigma = (i_1, i_3, i_2)$ because of $\tau^4 = \tau$. In summary it will be shown in the following table.

| Conjugated Permutation | equals to |

|---|---|

| $\Inv\sigma \tau \sigma$ | $(i_1, i_3, i_2)$ |

| $\Inv\sigma \tau^2 \sigma$ | $(i_1, i_2, i_3)$ |

| $\Inv\sigma \tau^3 \sigma$ | $e$ |

| $\Inv\sigma \tau^4 \sigma$ | $(i_1, i_3, i_2)$ |

Considering the permutation $\Inv\sigma \tau \sigma$ and its exponentiation, we can see that the permutation is changing at the regular intervals. We use this at secure grouping protocol.

Secure Grouping Protocol

The secure grouping protocol was proposed in this paper (Japanese). The feature of this protocol is that a fair third-party is unnecessary and when players are divided into three or more groups, the players who belong to a group can know who belongs to the same group. On the other hand, they do not know which group the other players belong to.

In this section, I first explain the number cards, which are needed to make this protocol, then define the Pile-Scramble Shuffle and finally construct the protocol.

Number Cards

In this protocol, we use number cards7 which are printed with the following number.

$$

\def\card#1{\boxed{\vphantom{1}#1,}}

\card{1},\card{2},\card{3},\card{4} \cdots \card{n}

$$

The back of the cards are $\card{?}$ so all players can not distinguish between cards on the back and can not guess the numbers of the card turned over. We write the order of the cards using the permutation $x$ as follows.

$$

\card{?}, \card{?} \cdots \card{?}, (x)

$$

If the cards are sorted in numerical order, we write as follows using $id$ specially.

$$

\card{1}, \card{2} \cdots \card{N}, id

$$

Pile-Scramble Shuffle

I will talk about Pile-Scramble Shuffle. This is an operation to choose one permutation with uniform probability from all permutations and apply it for the cards' order.

$$

\def\pss{\left\lvert\Big\lvert \card{?} \middle\vert \card{?} \middle\vert \cdots \middle\vert \card{?} \Big\rvert\right\rvert}

\pss, (x) \rightarrow \card{?}, \card{?} \cdots \card{?}, (rx)

$$

This indicates that we choose a permutation $r$ at random and apply it for the cards sorted by permutation $x$. Intuitively speaking, we just shuffle the cards.

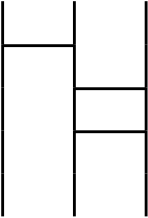

Randomizing Permutation

We define an operation to randomly select a permutation $\rho$ that has the same type as a certain permutation $\tau$. Intuitively, it is similar to insert a new random horizontal line into an Amidakuji. We can insert a new line to the place where there is horizontal line between the vertical lines but we can not insert a new line the place where there is no horizontal line. By this way, we can randomly generate a permutation that has the same type.

-

Prepare two rows of cards in the numerical order and turn over the cards

\def\twopair#1#2{%

\begin{matrix}

#1 \

#2

\end{matrix}

}

\def\twocards#1#2{\twopair{\card{#1}}{\card{#2}}}

\def\twopss#1#2{\left\lvert\left\lvert \twocards{?}{?} \middle\vert \twocards{?}{?} \middle\vert \cdots \middle\vert \twocards{?}{?} \right\rvert\right\rvert \twopair{(#1)}{(#2)}}

\card{1},\card{2} \cdots \card{n} \rightarrow \card{?},\card{?} \cdots \card{?} \

\card{1},\card{2} \cdots \card{n} \rightarrow \card{?},\card{?} \cdots \card{?}

```

2. Apply a Pile-Scramble Shuffle two rows cards together

```math

\twopss{id}{id} \rightarrow \twocards{?}{?}\, \twocards{?}{?} \cdots \twocards{?}{?} \twopair{(\sigma)}{(\sigma)}

```

-

Apply an arbitrary permutation $\tau$ to the below cards row

\twocards{?}{?}\, \twocards{?}{?} \cdots \twocards{?}{?} \twopair{(\sigma)}{(\sigma)} \rightarrow \twocards{?}{?}\, \twocards{?}{?} \cdots \twocards{?}{?} \twopair{(\sigma)}{(\tau\sigma)} -

Apply a Pile-Scramble Shuffle two rows cards together again

\twopss{\sigma}{\tau\sigma} \rightarrow \twocards{?}{?}\, \twocards{?}{?} \cdots \twocards{?}{?} \twopair{(r\sigma)}{(r\tau\sigma)} -

Open the above cards row and sort the up and down cards pair in order that is above cards are sorted. As a result, the below row is applied with the permutation that is $(r\sigma)^{-1} = \sigma^{-1}r^{-1}$. Finally get a cards row that $\sigma^{-1}r^{-1}r\tau\sigma = \sigma^{-1}\tau\sigma$ (where $i_1, \dots, i_n$ is arbitrarily chosen from $1$ to $n$ that do not overlap)

\twocards{i_1}{?}\, \twocards{i_2}{?} \cdots \twocards{i_n}{?} \twopair{r\sigma}{(r\tau\sigma)} \rightarrow \twocards{1}{?}\, \twocards{2}{?} \cdots \twocards{n}{?} \twopair{id}{(\sigma^{-1}r^{-1}r\tau\sigma)} = \twocards{1}{?}\, \twocards{2}{?} \cdots \twocards{n}{?} \twopair{id}{(\sigma^{-1}\tau\sigma)} -

Let the generated cards row $\sigma^{-1}\tau\sigma$ be $\rho$

\rho := \card{?}\, \card{?} \cdots \card{?}\, (\sigma^{-1}\tau\sigma)

Protocol

We will see the secure grouping protocol. We consider first that there are $n$ players and group them into $m$ groups $A_1, A_2, \dots, A_m$. There are $m_i$ groups with $r_i$ people where $i := 1, 2, \dots, k$, then $n = \sum_{i=1}^{k}m_ir_i$ and $m = \sum_{i=1}^{k}m_i$ hold. Note that we use $2r(n + m)$ cards for the sum of $2r$ cards from $1$ to $n + m$.

We assign $1 \dots n$ cards to player $1 \dots n$ and cards from $n + 1 \dots n + m$ to groups $A_1 \dots A_m$. It is summarized the following table.

| Number of card | is assigned |

|---|---|

| $1$ | Player $1$ |

| $\vdots$ | $\vdots$ |

| $n$ | Player $n$ |

| $n + 1$ | Group $A_1$ |

| $\vdots$ | $\vdots$ |

| $n + m$ | Group $A_m$ |

The protocol is as follows.

- Choose a permutation $\tau$ which has the type $\left< (r_1 + 1)^{m_1}, (r_2 + 1)^{m_2}, \dots, (r_k + 1)^{m_k}\right >$ where $\tau$ is a product of cyclic permutations each cyclic permutation includes a number that indicates a group

- Create $2r$ permutations $\sigma$ to be used for randomization once where $r := \text{max}(r_1, \dots, r_k)$. When creating $\sigma$, apply Pile-Scramble Shuffle only for the cards from the $1$st to the $n$th

- Create $\rho = \Inv\sigma \tau \sigma$ using $\sigma$ in (2). We can also create $\rho^2$ from $\tau^2$ using the same $\sigma $, so we also create $\rho^2, \dots, \rho^r$

- Player $i$ draws $i$th cards one by one from the left of the cards row $\rho, \rho^2, \dots, \rho^r$. Each player gets one card indicating a group and cards indicating all other members of the same group

Since the secure grouping protocol consists of shuffle, draw and open, it can be done by Mental Poker. Note that this GitHub Repository is an implementation of secure grouping protocol.

Voting

It is necessary to vote for playing Werewolf. In this section we consider the protocol to decide the choice that is a majority among several choices without a fair third-party. we need to vote in the follwing cases.

- When all players decide a player to execute

- When werewolves decide a villager to kill

We can vote with number cards, and we can also be done voting using Mental Poker's shuffle, draw and open.

Protocol

We assume that the voters are $n$ people up to $1, 2, \dots, n$, and each voter choose one from $1, 2, \dots, m$ options.

-

A voter $i$ two rows of cards $1$ to $m$ in the numerical order and turn over the cards

\card{1}\,\card{2} \cdots \card{m} \rightarrow \card{?}\,\card{?} \cdots \card{?} \\ \card{1}\,\card{2} \cdots \card{m} \rightarrow \card{?}\,\card{?} \cdots \card{?} -

A voter $i$ applies Pile-Scramble Shuffle to both rows of cards

\twopss{id}{id} \rightarrow \twocards{?}{?}\, \twocards{?}{?} \cdots \twocards{?}{?} \twopair{(r)}{(r)} -

A voter $i$ draws all of the above cards rows. And they put $k$ that they want to vote at the left end

-

The voter $1$ gathers all the cards on the left end of the voter's $i$ card line (a voter $1$ is selected at random, so any player can do this)

\card{?}\, \card{?} \cdots \card{?} ``` -

The voter $1$ applies Pile-Scramble Shuffle to the $n$ cards that are collected in (4)

-

The voter $1$ opens all cards shuffled by (5)

-

All players count the number of the same number cards opened in (6) and determine the max number

When running this protocol using Mental Poker, we have to be able to shuffle the shuffled deck again. This is called reshuffle, and there is research on Mental Poker which can reshuffle. In the intuitive explanation of reshuffle, we repeat shuffling the box and sending it to the next player without putting padlocks.

Werewolf using Mental Poker

Then we will finally make up Werewolf using Mental Poker.

- All players use the secure grouping protocol to divide $n$ players into $m$ werewolves and $l$ villagers (However, villagers must not be able to distinguish whether other players are villagers or werewolves, so we make $l$ groups which $1$ person belongs to)

- In the night, werewolves decide a villager to kill using voting (since werewolves can determine that a player who is a villager or werewolf)

- One of the werewolves notifies the villager to be killed, then the villager who were killed leaves the game

- When the night is over, if any villager is not killed, the villagers win immediately (it means all the werewolves are executed)

- In the daytime, all players vote and decide who will be executed

- The executed player leaves the game

- All players repeat (2) and (3) alternately

- Werewolves can declare to win if the number of werewolves is equal to or greater than the number of villagers. If a werewolf declares to win, all players who have not died reveal a number card that indicates their group and they count the number of werewolves and villagers in the game. If the number of werewolves equals to or greater than the number of villagers, it means a win of werewolves and if the number of villagers is greater than the number of werewolves, it means villagers win.

Conclusion

We see that we can play complicated games like Werewolf which seemed to be impossible with Mental Poker. Mental Poker can be implemented by some programming languages, so we able to play Werewolf on the computer without a fair third-party.

However, there are some issues. When a villager is killed and removed from the game, they know that a player who notified is a werewolf. If a villager can not know who the player notified them, this Werewolf game is more similar to Werewolf with a moderator.

Also, in this Werewolf, the judgment of win of the werewolf side is different from Werewolf with a moderator. We have to decide to win by how werewolves declare to win or no villager is killed at night. So there are more options to take disadvantageous actions against the sides which the player belongs to, for example, a werewolf player declare to win despite not winning. We can play the game correctly under assuming that “all players do not take disadvantageous actions to the side which they belong to”. But we may need to improve this.

As a further discussion, there are some rules that added various roles besides the villager and the werewolf, so it is a future work to deal with that.

Thank you for reading this article. Your comments, problem reports and questions are very welcome!

References

- Secure Grouping Protocol Using a Deck of Cards

- Secure Grouping Protocol Using Cards (Japanese)

- A TTP-free mental poker protocol achieving player confidentiality (Japanese)

- Contribution to Mental Poker

- Text for Group (Japanese)

- Python implementation of Secure Grouping Protocol (GitHub)

- urandom vol.3 (Japanese)

- Japanese version

Contacts

- Twitter: @_yyu_

- Email: yyu@mental.poker

- GitHub: y-yu

-

A fair third-party means a person like a judge who is guaranteed to behave similarly for all players in the game. ↩

-

This article does not require knowledges about RSA cryptography. ↩

-

In Werewolf game, a fair third-party is called moderator. ↩

-

A deck means all boxes after shuffling we talked earlier. ↩

-

For efficiency, this intuitive explanation has not been implemented as it is. ↩

-

We may omit $*$, $\Inv\sigma \tau \sigma$ means $\Inv\sigma * \tau * \sigma$. ↩

-

If I write card(s) hereafter, it means implicitly number card(s) to simplify. ↩